Until now, book-length personal records of the SAS in Sicily, written while memories were fresh, totalled exactly one. For fans and historians who find such first-hand accounts invaluable, Peter Davis’ exciting new book has doubled our treasure.

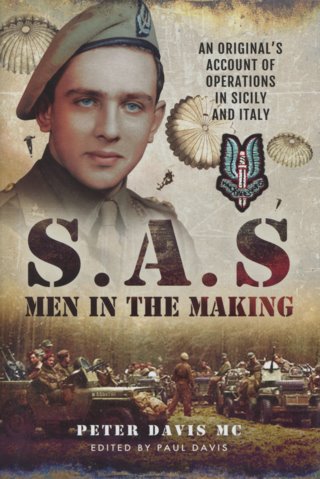

Book review: ‘S.A.S. Men in the Making. An Original’s Account of Operations in Sicily and Italy’ by Peter Davis MC, published 3 August 2015 by Pen & Sword.

Book review: ‘S.A.S. Men in the Making. An Original’s Account of Operations in Sicily and Italy’ by Peter Davis MC, published 3 August 2015 by Pen & Sword.

“SRS, prepare to embark”. This was the chilling phrase broadcast over HMS Ulster Monarch’s tannoy as the ship anchored in the waters off Cape Murro di Porco south of Syracuse on the night of 9/10 July 1943. It alerted the SAS men of the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) that they would soon be in action. Their target was a heavily defended Italian gun battery sited on top of the cliffs of the cape. The men had been told that the fate of the whole invasion of Sicily depended on them. In the eerie glow of combat lighting, they now waited in final suspense. Each man knew it was possible that he might not survive the night. On the order “SRS, stand by to embark”, the men headed towards the oiling doors where they would climb into their landing craft. Here they waited again, but already activity was subduing anxiety. At last the call came: “SRS embark”. Apprehension vanished.

Peter Davis was there that night.

As the last veterans of WW2 die, the opportunity to hear vivid stories directly from them dies with them. There is a profound sense that there will soon be, if not already, no more new tellings. So the publication of Peter Davis’ account of the invasion of Sicily is as surprising as it is rare. Until now, the only full account of Sicily written shortly after the war by an SAS veteran was Derrick Harrison’s excellent “These Men are Dangerous”. Harrison was a section commander alongside Davis. Both accounts, recorded while the memories were still fresh by articulate, intelligent writers, are doubly precious because they are full of the details usually lacking in accounts made many years later. There are details of place, details of atmosphere and, perhaps most valuable of all, details of emotions. The combination brings history to life.

Davis’ son Paul found the manuscript of his father’s account when going through his papers some 18 years after he died. It was apparently written immediately after the war based on wartime diaries, while Davis was waiting to go to Cambridge University. Its original title was “Stand By to Embark”. Although redolent of high drama, this phrase would have meant nothing to most people, so it is undoubtedly wise, in this age of internet search key words, that the title was changed.

The first two chapters describe how Davis’ unit, 1 Special Service Regiment, was amalgamated with the SAS and posted to Kabrit in Egypt at about Christmas time 1942. The heady days of SAS exploits in the desert were already over, as Eighth Army was at the gates of Tripoli and Tunisia. Davis saw no action with the SAS in North Africa, but he was part of Paddy Mayne’s SRS, a subdivision of 1 SAS Regiment, from day one. The story of the SRS, from training, through the invasion of Sicily, to finally leaving the island, occupies chapters 3 to 8. Later chapters describe the invasion of mainland Italy and then the anti-climax of returning to the UK via North Africa at the end of 1943. Davis wraps up his text without covering actions in 1944 and 1945 in North West Europe, but an appendix provided by his son gives some information on these.

In terms of narrative, Davis’ Sicily account can be compared to Harrison’s, which is not surprising, as they were both in 2 Troop. Davis covers the taking of Lamba Doria (the battery on the cape), and also the taking of “the second battery” (AS493) further inland on the ridge of the Maddalena Peninsula. He does not mention the remaining two batteries on the peninsula, which were taken by another troop.

He describes the depressing effects of constantly seeing crashed gliders and the dead bodies of airborne troops who had taken part in Operation Ladbroke. At one point there was a fire-fight between glider troops and the SAS, whose unorthodox uniforms did not at first look British. Davis was not to know it, but the SAS actions in the Maddalena Peninsula had a dramatic effect on the unfolding of the airborne troops’ battle for the Ponte Grande bridge and the race for Syracuse.

During the landings at Augusta two days later, Davis was in the second wave, and his account is particularly strong on the jittery night spent in the deserted city. He then describes in detail what is hardly touched on by most writers, the days spent camped at various sites north of Augusta, constantly under enemy air raids and overwhelmed by flies and mosquitoes. These were not days of combat, but they greatly flesh out our understanding of what it was like to fight on the island.

There are also many photographs, many of them apparently never published before.

Davis’ tone is pitched well throughout. Although he tells the funny stories that soldiers are so fond of, they do not dominate or distort the history. One of Davis’ great strengths is that he never shies away from admitting to the effects of fear and apprehension, whether learning to parachute, waiting to fight, or staring into the enemy-filled night. There are no false heroics here.

He struggles, understandably but successfully, to describe the remarkable nature of the men of the SAS, whom he clearly loved: the roguishness, the disciplined indiscipline, the heroes conjured out of those whom society might well look down on. His account is a tribute to these men, and an attempt to hold on fiercely to times he would never see again, and would always miss.

This book is a wonderful find. Many thanks to Paul Davis for bringing his father’s account out into the world.

Links: