The CO of the glider pilots blamed their ‘limitations’ for the ‘near disaster’ of Operation Ladbroke. That was later. What did he say at the time?

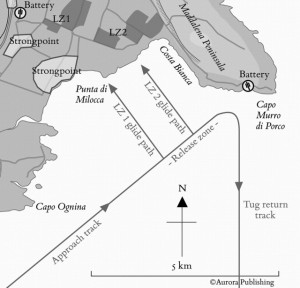

In Part 1 we saw how Operation Ladbroke, the glider assault that opened the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, was a last minute decision. It left little time for training. During the operation things went badly wrong. Roughly half the gliders landed in the sea, and hundreds of men drowned. Most of the rest of the gliders got nowhere near their designated landing zones (LZs).

George Chatterton, the Commanding Officer of the Glider Pilot Regiment, wrote in his book ‘The Wings of Pegasus‘ (published in 1962): “I was under no illusions concerning the main reason for the near-disaster [of Operation Ladbroke]. Whatever mistakes I may have made, and no doubt I did make many, what I could not help was the limited training and, therefore, the limitations of the glider pilots.” The charge to be answered is that the limited training of the glider pilots was the main factor in the near-disaster. The key question is whether the accusation is true. But before examining that, there are other questions. Did Chatterton believe the accusation in 1943, and if not, why did he make it in 1962?

The context of the accusation in his book, published 19 years after Operation Ladbroke, may give some clues. He records that on landing in Tunisia after returning with the glider troops from Sicily he was ordered: “On no account will you allow any of your officers and men to get into any argument with the Americans about this operation.” He said he was given no reason for this, but that there were “many unpleasant rumours in the air that they [the American tug pilots] let us cast off too early”. He said he tried not to listen to these.

But he did admit to arguing with some of his own men. “Two officers had to be dealt with. Even today, one senior officer (who incidentally took no part in the training or the operation) is a severe critic of mine”. The accusation against his own men is on the same page as these observations and follows them.

From this it could seem that Chatterton thought American-British relations governed what could be said or even thought, even nearly twenty years later in 1962, when the USA was still the dominant military partner, this time in NATO. Certainly in 1943 promoting cooperation was a highly laudable and war-winning endeavour, because allies fighting each other instead of the enemy could be disastrous. General Eisenhower had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the forces invading Sicily less as a battle commander and more as a chairman of the board, and he constantly strove to reconcile the British and the Americans. It is also clear from what Chatterton says in his book that he is defending himself against his critics, especially critics of his training programme.

Report 1 – D Day, 9 July 1943

The above quotations are what Chatterton wrote 19 years after the fact. What did he say at the time? The first of his reports regarding the training of the glider pilots is dated, surprisingly, 9 July 1943. This was the day of the airborne invasion itself, and surely Chatterton had a hundred more important things to do than finish off reports (such as make final preparations for himself and all his men to fly, or to raise the release heights to counter the high winds the gliders suddenly faced that day).

Perhaps the date is wrong. Perhaps the report is an “in case I do not return” document, because Chatterton was flying into danger in Sicily at the head of his men. But he also wrote a last minute report nearly a year later, just before D-Day in Normandy, when he was kept back in the UK. What both the 1943 and 1944 reports do is justify the training, and say how good it was.

Exercise Adam, a month before the invasion, was the first daylight rehearsal for Sicily, when nearly 150 gliders would be used. The rehearsal involved a third that number, 54 gliders. Chatterton wrote in his report that it “was entirely successful in that it showed that both mass take-offs and landings could be effected rapidly and without loss of life”. In the second daylight rehearsal with 72 gliders a week later, Exercise Eve, some gliders failed to make the LZs, but “despite this it confirmed the efficiency of the training methods”. A third rehearsal by moonlight with a mere 12 gliders was meant to prove that another 130 or so could also land successfully. But presumably the best pilots were picked for the 12 planes and gliders, and even so two of the 12 gliders missed the LZ.

Chatterton wrote: “Experiments were made … and it was found that moonlight landings were more simple than was thought at first and that, with careful handling, an aircraft could be put down in pitch darkness without aids.” Later, in his book, he took the opposite tack, and bewailed the immensity of the task that the glider pilots had been set, particularly with regard to “pitch darkness”. He did admit that due to constraints:

“it has been necessary to make major adjustments, which may very easily impair the efficiency of the operation. If this is so, it will not be the fault of any of those serving in The Glider Pilot Regiment. It can only be hoped that, should the cost in lives be great, it will at least be a lesson and that all efforts will be made to see that it does not occur again.”

He finished by saying: “The Commanding Officer [i.e. himself] has every confidence in his pilots … He also has great confidence in Gliders for future operations.” This last comment is telling. Doubts were continually raised long before Sicily about the usefulness and great expense of airborne units, and doubts would be raised again after Sicily. But the Regiment was Chatterton’s project. He had nailed his colours to the mast, and he was presumably keen for the ship not to sink, as it would take his captaincy with it.

Report 2 – After the Debacle

His next report was just over ten days later, after returning from Sicily to Tunisia. Ten days is a long time in war, and in this time not only Operation Ladbroke but also the airborne operations Fustian, Husky 1 and Husky 2 had all gone wrong in their own spectacular ways. Planes were shot down by Allied guns, or were scattered by bad navigation, and some troops landed in the lap of an elite German paratrooper formation. Chatterton himself, piloting Waco 2 in Operation Ladbroke, had landed in the sea. This second report was dated 20 July 1943, three days before a Board of Enquiry convened to discuss the airborne debacles and, by extension, the future existence of the airborne arm.

Chatterton started the report by describing his arrival in Africa four months earlier, when, he said, he had “very reserved opinions of the glider”. These opinions, he said, were based on scientific study and on having flown in almost every combination of glider and tug. This confession is strange, coming from the man who had to train his glider pilots and then lead them into battle. He repeated himself for emphasis: his experiences “made him hold an extreme reserve in the use of the glider”. There was not a hint of this “reserve” in the first report, just before Operation Ladbroke, which had been very confident.

He went on to repeat that the training and rehearsals, limited as they were by time, had been successes. He then described flying to Sicily and reaching the release zone: “… the moon was poor and gave the Tug ship an impossible job let alone the Glider pilot … for both pilots the arrival in the target area was quite unexpected and presented a position which was immediately designed to upset any plan that might have been set out.” He listed several observations, conclusions and lessons, including the vulnerability of the C-47 and the need for tug pilots to be trained to fly through flak.

Regarding any deficiencies in the training of his glider pilots, however, all he said was that tug and glider pilots needed to know each other better, and: “Tug Pilots and Glider Pilots must have constant practice. This need not be daily but long gaps between flying must not be allowed. Tug Pilots must be trained in night flying and Glider Pilots kept in practice on moonlight landings.” Given enough resources and time, this would no doubt have happened. Note that the tug pilots are included equally with the glider pilots in these comments. There is certainly no hint he thought the glider pilots were chiefly to blame for the Operation Ladbroke mistakes. In fact he elaborated how successful the glider pilots had been in combat, despite all the set-backs.

By the end of the report, apparently vindicated by the combat results, he countered his opening reserve with an optimistic summing-up for the future, saying that in gliders the Allies “have a formidable weapon, which used correctly can prove successful beyond words”. There follows more praise for his glider pilots, as in them the Allies have “exceptional Pilots who can both fly and fight and who have proved their worth“. The report ends with what could seem like bullet points in his own CV – he concluded that the Allies also had, in the Glider Pilot Regiment, “war experienced staff” and “a proved organisation”.

The Memo – Judgement Day

But Chatterton was not finished yet. About two weeks later he wrote a third report, unsigned but surely his, dated 2 August 1943. This was two days after the last day of the Board of Enquiry, and was the same day as the date of “Training Memorandum Number 43” (Memo 43). Memo 43 was the result of the Board of Enquiry’s conclusions about the lessons of Sicily, delivered in the form of an airborne training policy document.

Interestingly, during the enquiry both Major General ‘Boy’ Browning, Eisenhower’s British airborne adviser, and Colonel Ray Dunn, the CO of the US Troop Carrier Wing, admitted to being overconfident and overoptimistic due to what appeared to be the positive progress of training. This optimism is similar to Chatterton’s upbeat assertions in his first report, and raises questions about how all these senior officers came to be so mistaken. Perhaps, faced with no choice, they simply had to be as committed as possible. Once the machinery of something as massive as a major amphibious and airborne invasion was in motion, risks had to be accepted, and forcing yet another total rethink so late in the day was unimaginable.

The only criticism the Board of Enquiry had of the performance of the glider pilots was that they had been trained to land too fast. This increased the chances of a glider hitting something and made the impact worse if it did. Heavy landings also damaged or trapped equipment such as guns and jeeps. When the point came up during the enquiry, Dunn promptly said this policy had already been rectified.

Chatterton had not been called to the enquiry, and there is no record of either of his previous reports being presented. In fact, we do not know if anyone outside his office read any of his three reports. Also we do not know if he had read Memo 43 before he finished his own report, although his main conclusions are very similar to Memo 43’s. What Memo 43 has to say about the tug pilots and glider pilots is worth quoting in full:

“Training for specific operations must cover all details and contingencies, and culminate in a rehearsal of the operation with conditions approximating as closely as possible those of the actual operation. Intensive training in low flying navigation at night, especially over coastlines, must be included. Special attention will be given to the training of glider pilots, including the maintenance of courses despite the effects of adverse winds, and the coordinations between glider and tug in determining the glider release point.

The standard of training of troop carrier crews is the same as that of other operational combat crews. Wherever possible in training for a specific operation the troop carrier crews should make a flight on a bombing mission over the route and area selected for the operation in order to familiarize them with terrain features.”

None of this indicts the glider pilots, and most of it is about tug pilots. Somewhat absurdly, one of Memo 43’s only two glider-specific suggestions appears to be that the glider pilots should handle head winds better. There is in fact nothing a glider pilot can do about a head wind, except maintain ‘Best Gliding Speed’ and avoid manoeuvres that exacerbate the rate of sink, elementary flying skills which the Sicily pilots must surely have possessed.

Report 3 – Riposte to The Memo?

So what did Chatterton’s third report, dated the same day as Memo 43, have to say? He began by admitting his disappointment about Operation Ladbroke, but assessed the operation as follows:

“A most difficult operation was carried out by night and was 75% successful. The 25% failure was mainly due to

1. Weather.

2. Inexperience.

3. The great difficulty of the whole operation.

4. Bad luck – which always plays an important part in war.”

So far, there is no explicit blame for the glider pilots, but we have not yet heard what is hidden under that word “inexperience”. There is also not much sign of “near-disaster”, and if Operation Ladbroke was only a 25% failure, then whatever part the glider pilots played in that through inexperience hardly constituted a major impact on the outcome. He went on to say that the aim of the training had been achieved, despite time being too short. He then appears to contradict this claimed achievement by saying more of the training time should have been spent rehearsing “BY NIGHT AND BY THE COAST” (his capitals), rather than practising elementary flying and converting to the Waco. There had been no full-scale rehearsals over water at night, of course, because of the high risk of serious losses of both men and gliders. Chatterton continued:

“The target area was reached but owing to bad visibility and haze, together with the varying wind, it was very difficult to judge the distance from the shore. The task of the Glider Pilot, therefore, was almost impossible as he could not see the target nor could he guarantee that he had released correctly. At the same time the moon was covered by a thin haze, preventing the pilots from seeing the ground and the task of selecting the correct landing area became increasingly difficult.”

Again, so far it does not sound as if there was anything the glider pilots could have done about any of this, but Chatterton goes on:

“The run-in was extremely difficult and proved that this type of flying needs careful practice. It is easy to misjudge the distance and places on the coast in moonlight. It increased the difficulty of the release of the Glider Pilot. The lack of experience in this type of operation was the chief cause of the plan going wrong … This applies to both Tug and Glider Pilot.”

Finally we have something that sounds like the accusation he levelled in his 1962 book, where he claimed that the main cause of the failures of Operation Ladbroke was the limitations of his undertrained glider pilots. Unlike the book, in the report the tug pilots are included in the charge. Also unlike the book, the third report specifies that what Chatterton found lacking was recognition skills, not flying skills.

Near the end Chatterton says: “the operation must not be condemned out of hand. Generally speaking it was a great success and much was proved. If it went wrong, those who took part should not be blamed – they did their best”. The fault, he said, lay in the past, with a lack of attention and investment, i.e. equipment, training and time. He was sure that if these investments were now made, great success would follow.

It is clear from his three 1943 reports that Chatterton did not especially blame his pilots. He was obsessed with their training, as that was his particular responsibility. So he was continually justifying his training programme or, where it was hard to, because of mistakes, he quite rightly looked for ways to improve in future. He also no doubt felt that he had to sell up the potential of the glider as a weapon of war, in order to secure that future.

Both Memo 43 and Chatterton’s final report emphasised improving the chances of pilots finding the release zone, and, from the release zone, reaching the LZs. To Chatterton this meant the powers in charge should acknowledge their past failure to invest (not his fault), and then, going forwards, to invest in the training that was needed to make these improvements.

Evolution & Devolution of Blame

So how did he get from there to blaming his pilots in his book? The key change is that the tug pilots have vanished from his comments in the book, leaving only the glider pilots to shoulder the blame. Perhaps this was indeed because he felt he dared not annoy the Americans (although he had left the Army shortly after the war, and surely his civilian career cannot have been in jeopardy). Perhaps he did not realise how bad his comments sounded, and thought it was obvious that the limitations of his pilots were not their fault. Perhaps he thought it sounded weak or invidious to blame the tug pilots. Perhaps in justifying his actions he felt he had to point up the limitations and constraints against which he struggled. But it is also possible that he was highlighting the only way in which he could make a difference.

An alternative solution to finding the LZs, for example, might have been to move the goalposts, so to speak. If the route to the target was too hard, or the release points too challenging, or night too difficult, or the LZs (and DZs) too small, or the flak too dangerous, then make the routes idiot-proof, the LZs gigantic, land by day and keep everybody well away from enemy concentrations. This logic seems to have been followed both during some of the Normandy operations and, notoriously, at Arnhem, where many believe the airborne troops landed simply too far away.

But such decisions were beyond Chatterton’s remit, and he could not control them. Nor could he force the tug pilots to improve their navigational skills (indeed, well over a year later the Americans still relied on the same low ratio of navigators as during Operation Ladbroke). What he could control was the internal organisation of the Glider Pilot Regiment, and the training of his glider pilots.

He emphasises both of these things in his 1944 report. And his book emphasises how he carved himself a new role in overall charge, as Commander Glider Pilots, so that he could push through his improvements. He does not go quite as far as saying that his glider pilots’ spectacular feat of flying at Pegasus Bridge in Normandy was entirely due to him, but it comes across strongly that he made the changes, appointed the experts and oversaw the training that made it possible. Certainly, he deserves his share of credit for the outstanding performance of the glider pilots during the war.

This reason, or a mix of some of these reasons, may explain why Chatterton later appeared to lay all the failings of Operation Ladbroke at his own pilots’ door. But, whatever his reasons for saying it out loud, could it in fact be true?

In Part 3: did the glider pilots in fact get it wrong?

A version of this article appeared in “The Eagle”, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regimental Association.