A previously unseen film shows what the heroic defence of the Ponte Grande bridge by British glider troops was all about – tanks and vehicles crossing, headed into Syracuse. This is the remarkable story of how that footage came to be taken.

For the record.

On 9 July 1943, Captain Fletcher of the British Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU) was photographed in an olive grove in Tunisia by his colleague, Sergeant Bower. In a few hours Fletcher would be taking off in a glider with British airborne troops who were spearheading the invasion of Sicily in Operation Ladbroke. The operation’s main objective was the capture of the Ponte Grande bridge near the port city of Syracuse.

Fletcher’s orders were to cover this operation, the largest glider assault in the war to date, for the record and for the folks back home. Now, in the olive grove in Tunisia, wearing the maroon beret of the “Red Devils”, he stood at attention while he was clinically photographed from the front [photo], from the side and from the back. This was “for records only”, meaning in this case that the photos were not for publication, and so did not need to be passed by a censor.

In the photos a stills camera is slung around his neck, and he holds a heavy-looking 35mm De Vry cine camera in his left hand. Pistol holster, binoculars, a large water bottle and a small knapsack bulge front and back. Somewhere on his webbing, 1500 feet of 35mm monochrome negative film is stored. On his hip what looks like a map case or clipboard cants out from his belt. If it is a clipboard, perhaps it was used for keeping notes of what was shot, information that would later form the core of the “Secret Dope Sheets” that accompanied the films when they were submitted for development and then censorship.

Bower himself was due to fly a day or two later with British paratroopers who were to capture a bridge near another Sicilian port city, Augusta (Operation Glutton). That operation was cancelled. So Bower frantically pushed to get himself included on the next parachute assault, the attack on the Primosole bridge, near the port city of Catania (Operation Fustian). He got his wish, and on 13 July flew in a Horsa glider carrying a jeep and 6 pounder gun, designed to give anti-tank capabilities to the lightly armed paras.

It was all so rushed that Bower did not get time to properly finish logging the footage he had shot on the airfield before take-off. He had also had to switch hurriedly from his usual parachutist’s 16mm cine camera to the larger 35mm De Vry used by gliderborne photographers. Nearly a week later Fletcher wrote of Bower’s Horsa:

“This Glider with Sergt. Bower inside it has at the time of writing disappeared without trace.”

Back then, as now, cameramen died for the record.

It’s possible that Fletcher was as much a last-minute 35mm cameraman as Bower. A day or two before taking off for Syracuse, he filmed General Montgomery giving speeches to the glider troops of 1 Border Regiment and 2 South Staffordshire Regiment. Fletcher said he operated the camera himself for “much-needed practice”. Given his rank as captain, Fletcher was presumably more used to the role of director than cameraman, a job normally performed by sergeants. It was felt that sergeants would be better able to deal with both officers and “other ranks”, who might be intimidated by officer photographers.

The initial orders for the airborne division showed that it was planned to have two cameramen with the glider troops in Operation Ladbroke on the first day, then one cameraman each accompanying the two parachute assaults on the following days. However, of the camermen scheduled to fly on Operation Ladbroke, Sergeant Spittle of the AFPU “was declared unfit the day before take-off”, and Fred Bayliss of Paramount News was killed in an air crash on his way to join the troops. So even if Fletcher had been expected to go, perhaps at first it was not as a cameraman.

Glider 35

Loading lists for the Operation Ladbroke gliders are confusing, as places for four AFPU men are shown, despite the original plan having specified only two. The lists show that two seats were allocated in gliders 80 and 95 that were carrying Border men, while two more were allocated in gliders 35 and 39 with men of the South Staffords. But we have no records of any cameramen other than Fletcher in Operation Ladbroke, either by name or by having the results of their work.

Of the four gliders, three reached land. The fourth, however, glider 39, was released by its tug, and the tow rope lashed back and damaged an elevator, causing a catastrophic descent into the sea (for more info see here). The records contradict each other, but one interpretation is that everybody in glider 39 drowned, apart from, miraculously, its senior glider pilot, John Ainsworth, who swam ashore and won an MM for his actions that night. So if there was an AFPU man aboard, his equipment probably sank, and he may have been killed.

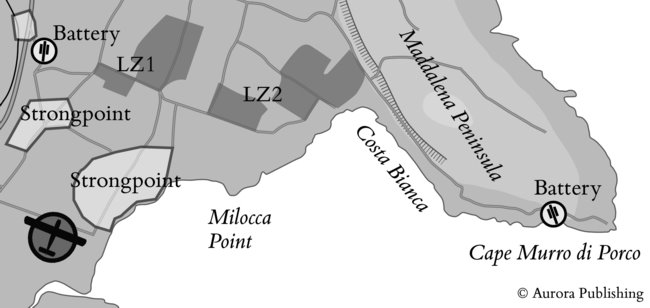

The tug towing glider 80 got lost off Sicily and returned to Malta before coming back again to Sicily. So glider 80 landed late, but apparently successfully, on or near the appointed landing zones (LZs). Glider 95 also apparently landed OK, and not much further away, on the neck of the Maddalena Peninsula. So if these two gliders had been carrying AFPU men, then they landed OK. But we have no records of their presence in Sicily, nor examples of any photos they took. So perhaps, with Spittle and Bayliss not available, there were in fact no cameramen in gliders 80 and 95. Which meant that only Fletcher was left to capture this historic attack on film.

Fletcher flew in Waco glider 35 with men of the Pioneer Platoon of the South Staffords. He filmed some shots inside the glider. The pioneer opposite him ate what looked like a rock cake and cleaned his Sten gun. The second pilot (in the right hand seat) was black with face paint. However the flight was so violently bumpy (and vomit inducing) that Fletcher gave up on any thoughts of filming the crossing. In any case the sun was setting and darkness soon fell. So he loaded his camera with the fastest film he had, Kodak Super XX, in the hope of filming flares and explosions in the night after the glider landed. The glider touched down well enough, not too far south of the LZs, but its landing run came to an abrupt halt when it hit a stone wall, and three or four men were injured. Fletcher lost his stills camera in the wreckage, and perhaps most of his spare cine film as well, as he hardly shot any footage in the hours and days that followed.

Fletcher explained his lack of exciting action shots:

“The Pln. Commander and the remainder of the glider load did not succeed in joining up with the British forces till the evening of 10th July, by which time the AIRBORNE action was over.”

The 10th was D Day, and the Ponte Grande bridge had finally been captured by the British at about 5pm. Frustratingly for historians, Fletcher does not describe what happened en route, nor does he say where the British forces were met (was it at the bridge?), nor whether those forces were seaborne or other airborne troops. He also does not say what time in the evening they met.

Fighting the Italians

Parts of the story can be reconstructed from maps, signals and the account of Staff Sergeant Leslie Howard, who was first pilot of glider 35, Fletcher’s glider. More than 50 years later, while visiting Sicily, Howard recounted his memories of what happened. He landed the glider about a mile south of the LZs, which was not bad in terms of distance from the Ponte Grande bridge. Unfortunately it was just on the wrong side of the ring of strongpoints that surrounded the Syracuse Military Defence Zone, and there were two of these strongpoints (clusters of pillboxes surrounded by barbed wire) between the survivors of the crash and their destination, the bridge. Piecing together the evidence, it seems the Staffords pioneer officer led the men north, skirmishing with Italians when they bumped into the edges of strongpoints, but successfully infiltrating between two of them.

This brought them to a large house where a furious fire fight ensued. The British won the dispute, and the Italians evacuated the building and vanished into the night. Inspecting the house, the airborne men concluded they had just captured a barracks, and they decided to stay and hold the position. Howard later said that seaborne forces in the shape of soldiers of the Green Howards reached them at about 7:30 in the morning, but his recall was off after 50 years.

It was in fact men of the Royal Scots Fusiliers (RSF). The RSF had to push on as fast as possible to reach the Ponte Grande before the Italians could recapture it from the airborne troops holding it, so they asked the Staffords men to garrison the HQ until relieved. Howard recalled that in the end they held the position for two days before they headed up to Syracuse. There he joined the surviving glider pilots who had been assembled at a villa in the town.

Fletcher makes no mention of any of this, and we do not know if he stayed at the Italian HQ with the Staffords pioneers, or if he left with the forward elements of the RSF. Howard’s story of arriving two days after D Day also clashes with Fletcher’s, who says they reached the bridge on the 10th, D Day itself. Even if Howard’s story is correct, it is unclear if “two days later” includes or excludes D Day.

Tanks for the Memory

So what does all this tell us about the photo of a Sherman tank crossing the Ponte Grande bridge, filmed by Fletcher, and shown at the top of this article? The confusion in the records means that it is difficult to put a date on the photograph of the tank, or to identify the unit the tank belonged to. What we can do is tell the time of day when Fletcher filmed the bridge. The sinking sun shines directly down the Mammaiabica canal (in the way that it does in the picture) at around 6pm each 10th of July. You might think this could help a lot – after all, there were not that many tanks in the area at the time, and surely their war diaries would record when they headed into Syracuse.

Unfortunately, just as we are not sure if Fletcher arrived at the Ponte Grande bridge on D Day (the 10th), or on the second day (the 11th), or “two days later” (on the 12th), we have more than one possible time for a crossing by a tank unit. At least we know it cannot be later than the 13th, as in the evening of this day Fletcher boarded an LCI (Landing Craft Infantry) in Syracuse harbour. Along with the rest of the surviving glider troops he was then shipped back to Sousse in Tunisia.

Regarding tank units, British armoured support for the seaborne units of Montgomery’s 8 Army consisted of 4 Armoured Brigade, which in turn consisted of two battalions of Sherman tanks: 3 County of London Yeomanry (3 CLY) and 44 Royal Tank Regiment (44 RTR). Both landed on beaches not far from the town of Cassibile, a few miles south of the glider LZs. 44 RTR got nowhere near Syracuse on D Day, but half of B Squadron of 3 CLY was hurriedly sent up towards Syracuse to support the infantry that had landed earlier.

Since the Ponte Grande bridge was captured by the RSF at about 5pm, and Syracuse was captured about 9pm, it seems possible that Shermans of 3 CLY crossed the bridge at about 6pm on the 10th. However the 3 CLY war diary gives no indication of this (though war diaries are not infallible). Instead it describes how B Squadron advanced north further inland, west of the Ponte Grande. Other Sherman tanks crossed the bridge the next day, the 11th, but much earlier in the day. On 12 July, however, most of the Shermans of 44 RTR finally left their assembly areas near the beaches at about 5pm and reached Syracuse at about 6:30pm, thus making perfect candidates for Fletcher’s filming.

Fletcher later complained that once he had reached Syracuse he could not find any transport, and so was unable to go further afield than the bridge to film any of the other sites of airborne actions. Fletcher’s account was made at the time, and Howard’s 50 years later, so Fletcher’s implication that he reached the bridge on D Day carries more weight. But even if Fletcher did reach the bridge on D Day, he might not have filmed at that point, instead carrying on to Syracuse.

Perhaps it took him two days to cadge a lift from Syracuse and get back to the bridge. Perhaps he waited for the intense heat of the afternoon to cool before lugging his heavy De Vry camera on foot the mile or so from the city to the bridge. Whatever means Fletcher used to get there, we have two front-runner theories: he filmed either a Sherman of 3 CLY crossing on 10 July, or a Sherman of 44 RTR crossing on 12 July.

Either way, finding this film after all these years gives us our first ever photograph of the Ponte Grande bridge as it was in 1943. And not just of the bridge, but also of the highly symbolic drama of a Sherman tank crossing it. The photo shows why the bridge was such an important target – it allowed heavy vehicles to reach the vital port city of Syracuse and quickly expand the bridgehead. The chances of Fletcher catching that dramatic moment were extremely slim indeed, unless he had camped out and waited.

Alternatively it’s possible that he mainly went to the area of the bridge to film the only Horsa glider that landed where it was supposed to (see the story of Galpin’s glider). While there he could see a column of vehicles coming up Highway 115 in the background, and he may have rushed to the canal bank to film the tanks crossing. Whether by skill or luck, or a bit of both, Fletcher did well. He, however, was not happy with his performance. He wrote on the sheet which he despatched with his meagre 100 feet of film stock:

“The accompanying three rolls contain, it is feared, nothing but mediocre and disappointing material.”

The contents of Fletcher’s three film tins may well have disappointed the editors of newsreels, who preferred both more human interest and, especially, more violent action. They hankered for the redoubtable face of the common Tommy, for bangs and flashes, men and machines firing and charging, the heroism of our men, the invincibility of Allied armies, the enemy in defeat, the gratitude of the liberated. Fletcher’s footage never made it into a newsreel, even if it was ever submitted for editorial consideration.

But to historians it’s an extremely precious record. We owe so much to the men who fought for us in WW2. But what would we have of their story without the men, like Fletcher, who also went into battle, not to fight, but for the record?

.

Update: A late amendment to the operational orders of 1 Border reads:

“Glider 95 – for one man AFU, read CSM H Coy.”

In other words, there would be no AFPU cameraman in Glider 95.

.

Staff Sergeant Leslie Howard’s account courtesy of the editor of The Eagle, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regimental Association.

Photo of Leslie Howard courtesy of Keith Howard.

.

More Info

For more information about the work of the AFPU in WW2, see Dr Fred McGlade’s book “The History of the British Army Film & Photographic Unit in the Second World War” (Helion, 2010).

Alan Whicker’s book “Whicker’s War” (HarperCollins, 2005) is also informative, and, in true Whicker style, an entertaining read. Whicker was in the AFPU in Sicily and landed on D Day with the seaborne forces far to the south of Syracuse. After the war he became a major TV personality and travel journalist. His mannered presentation in the weekly TV series he fronted, “Whicker’s World”, was so well known that he even got a satirical Monty Python comedy sketch all to himself. Whicker’s talent showed early in Sicily. While most AFPU photographers snapped their shots and moved on quickly to the next scene of action, Whicker submitted an extraordinary series of photo-journalistic pieces. Each photograph was a close portrait of a Sicilian from a variety of walks of life, but instead of a perfunctory caption, each was accompanied by a press-ready essay on the back. Small wonder that he went on to celebrity status after the fighting was over.

Notes on the IWM Photograph

The new photograph of the Ponte Grande bridge (above) comes from a 35mm film in the archives of the Imperial War Museum. The film is AYY 510/14. The image posted here is low resolution for the web. To reproduce it, apply to the IWM for a licence for commercial use, and for a list of film labs who can make high resolution copies and frame grabs.

You can watch the film here.

Lt. Powell-Davies also covered Operation Ladbrooke as did the Australian War Correspondent Rod Macdonald. I don’t know if Powell-Davies went in by glider but I know Macdonald did. Both were also photographed by Sgt Bower in the same olive grove in 1943. Perhaps then we have names for your 4 spaces in the gliders?

Powell-Davies went on to cover the invasion of Greece in late 1944 while Rod Macdonald was killed at Monte Cassino in May 1944

Nick – thanks very much for your interesting suggestions. However, I think I’ll stick with my interpretations.

I wonder what your source is for Powell-Davies being in Ladbroke, as it’s contradicted by evidence in the IWM. In the photos that you mention [IWM NA 4286+] Powell-Davies is kitted out as a parachutist cameraman, unlike Fletcher, who is ready for his gliderborne role [IWM NA 4282]. There were no parachutists in Ladbroke (9/10 July). There are photos of gliders taken by Powell-Davies in the IWM, but only ones taken in North Africa – there are no photos of Sicily by him in the IWM. He is also credited with shooting film footage back in Tunisia of paratroopers embarking for Operations Glutton (10/11 July) [IWM AYY 503] and Fustian (13 July) [IWM AYY 513/3], so he cannot have been in Ladbroke.

As for Macdonald [IWM NA 4291], he flew with Brigade HQ in glider 6. The loading tables for the four AFPU cameraman places show they were allocated to the Staffords’ pioneers (gliders 35 & 39), and companies A & D of 1 Border (gliders 80 & 95). The cameramen were part of the establishment of 4 AFPU, which was attached to 1 Airborne Division for Sicily, while Macdonald was attached directly to the division for Ladbroke. After all, Macdonald was a roving war correspondent and writer, not an Army camerman. We’re certainly lucky that he got through, as his are some of the best eye-witness accounts of Ladbroke.