The C-47 towing Glider 8 had an easy run in Operation Ladbroke. For its captain and his crew, it was the calm before the storm.

Glider: CG-4A Waco 8, serial no. 73602.

Glider carrying: Part of D Company HQ, 2nd Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment.

Troops’ objective: Gun battery Mosquito (for a guide to the objectives, see [here])

Manifest

Coy 2i/c

Batman

2 Nursing Orderlies

2 Sigs.

6 ORs

= 2400 lbs

1 h/c. 400 lbs

2 bicycles. 62 lbs

No. 18 Set. 50 lbs

2 i/c D Coy: Capt Wright, P.R.T.

Glider Pilot’s Report

Glider allotted Landing Zone: LZ 1.

First Glider Pilot: S/Sgt Dawkins

Second Glider Pilot: Sgt Kelly

“Statement by Passenger Exceptionally bumpy flight. Glider Pilot released at 2215 hrs about 1000 yds off shore height unknown. Pilot did not know his location. Glider landed on MADDALENA Peninsula where it hit a wall on landing. Both pilots broken legs.”

Oddly, no further mention is made of the injured glider pilots in other accounts of Glider 8. A later examination report shows severe damage to the aircraft’s front:

“Nose thru wall, landing gear, struts and right wing out, Fabric torn badly, nose crushed, framework bent slow landing.”

Tug Pilot’s Report

Tug: C-47, serial no. 42-68714, Sqn (Nose) No. 8, 10 TCS, 60 TCG, 51 TCW, Troop Carrier Command USAAF.

Takeoff: c. 18:54 from Airstrip A, El Djem Base, Tunisia. Priority 6, 4th in element 2.

Pilot: 1st Lt Runzel, Raymond A.

Co-Pilot: 2nd Lt Malone, Robert C., Jr

Air Eng: T/Sgt Green?, William (NMI)

Rad Oper: Sgt Sheridan, Peter (NMI)

Hit rel point?: Yes.

Time of release: 2211

Altitude: 1600

Vary from course: No

Light flak firing over LZ. 2 S/L on cape.

Runzel wrote a fuller account of his flight shortly after his return to base:

“At the approximate hour of 1845 on the night of July 9, 1943, we departed as per schedule on our first combat glider mission […] We reached our objective around 2012 hours, with the glider releasing at 1700 ft., the correct position and distance from shore.

Only points of interest on route were two hospital ships passed about an hour out and the numerous planes approaching and leaving Malta airdrome. The planes and island were brilliantly lighted.

Upon entering the drop area we sighted an unlit aircraft approaching us at exactly 180 degrees from our course. It proved to be another glider, and was just off our left wing as our glider released. Both gliders then turned shorewards and all was well.

As the glider was releasing we observed several guns firing off the point apparently towards the landing area. Then a searchlight seemed to appear, a large explosion simultaneously, then all was clear.

We then dropped our tow rope, made the exit turn and proceeded on our return course. After the turn, Lt. Colonel Bagby, who was a passenger in our plane, reported numerous explosions, searchlights and more intense gun-fire. Another flight was spotted coming in directly right of and under our right wing. We climbed to 6,000 ft. Upon rounding Malta we let down to 2,500 ft., our prescribed course home. Malta was covered with searchlights (apparently fixed) on our return. For nearly an hour prior to reaching the North African coast we ran into light cumulus clouds and a slight haze. About the fourth plane to land, we were on the ground at 0020 hours.

The crew wishes to report a successful and enjoyable trip.”

Bagby was yet another very senior officer who was getting a whiff of action by accompanying his men as an observer (for other examples, see [here] and [here]). Bagby was in fact Chief of Staff and second in command of the whole TCC in North Africa.

Runzel’s account may seem at times a little callous, given how many gliders were released to fall into the sea [story], where hundreds of airborne troops drowned [story]. If it sounds as if the flight for Bagby and his men was just a jaunt, it might be because Runzel’s account may have been prepared by request for possible use in a press release. Press releases were usually relentlessly upbeat, and often presented the war as an adventure or a game.

Certainly there was nothing flippant about Runzel’s performance three days later in Operation Fustian, when he was wingman to 1st Lt Lee Carr (who had towed Glider 4 in Operation Ladbroke). In Fustian Runzel stuck by Carr through a storm of AA fire and violent evasive manoeuvres. Undeterred, they went round again for another pass.

It was the last time Carr saw Runzel’s plane. Carr crashed into the sea, but survived. Runzel was shot down, but he, his co-pilot R C Malone, and the rest of his crew all died.

Carr wrote a letter to Malone’s sister, at her request, explaining what happened. His description of the pre-flight time could apply almost as much to Ladbroke as to Fustian. It paints a picture of young men at war who were no different to the many glider troops who felt so let down by them, and who demonized them. Carr wrote:

“I did not have the intimate relationship with R.C. [Malone] enjoyed by Judge and Ray Runzel. Frankly I was a twenty two year old second Lt., a loner, almost an idealist. […] My meetings with R.C. were either in the tent […] when we were detail-planning missions or doing a wrap up on return (over a can of beer), or on the flight line. We were all in the same flight at that time and to me R.C. was always a bit shy with a perpetual small smile lighting his countenance. I was an outsider, didn’t even know about Charlene (choke). My closest moment with him was after the formal briefing on the afternoon of the 13th when the four of us huddled together to analyze the incredibly uninformative briefing we had just witnessed, and to play the game of what if – what will we do, if – etc. […] With little time between the briefing under an olive tree and scheduled take off, we huddled, as I said, studied the map and locations of the drop zones and each reaffirmed that we had to make a successful attack, that we would go in no matter what.”

Action

The Staffords’ battalion war diary does not tell us much about the men in Glider 8:

“Capt Wright with the remainder of Coy H.Q. landed on the SE tip of the Maddalena Peninsula, were engaged in a few minor skirmishes and joined with seaborne forces reaching the Bn on the 11th.”

It is not explained why the men took until the 11th to reach the rest of the Staffords. By comparison, the men of Glider 6 under Lt Welch landed not far away from Glider 8, and they reached the Ponte Grande bridge early on the 10th in time to play a significant part in its defence [story]. Perhaps, as a mainly non-combatant part of a headquarters unit, Wright’s party did not have the firepower and fighting clout that Welch’s Brigade HQ Defence Platoon did. Perhaps they tried to pull the handcart the whole way along Sicily’s appalling back roads.

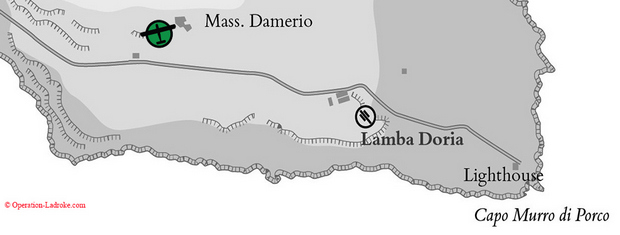

We may not know much about what happened to the Staffords in Glider 8, but for once we have a decent account from an Italian witness, even if he was only four years old at the time. Giovanni Nobile lived with his family in Masseria Damerio. Years later his memories of that night remained vivid. He recalled that two green gliders landed near the farm, one near the irrigation water tank, the other about 500 yards away. The occupants made off into the night. Giovanni’s father went to notify the garrison of the nearby ‘Lamba Doria’ gun battery, who sent some men to fetch the family and their farm hands.

They led them to a nearby wooden chapel “for safety, before the inferno began”. During the bombing of Syracuse [story] a stick of 24 bombs fell close to the chapel, so they were moved to some caves. In the morning they returned to the farm, finding British soldiers there. Some were airborne troops whose gliders had landed in the sea, who were given clothes at the farm. One of the farm workers spoke English, and the Nobiles persuaded the British to leave them their cows, apart from one which was requisitioned. By way of thanks they offered them some milk, but the British made them drink first. “Better safe than sorry”, they said.

.

Thanks to Paul Davis for permission to use photos from his father’s album. Peter Davis’ book “SAS Men in the Making” can be bought from the publisher here.

Thanks also to Lorenzo Bovi for permission to paraphrase Giovanni Nobile’s story from “Sicilia.WW2 Foto Inedite 5”. The book can be bought from the author: lobox@libero.it.