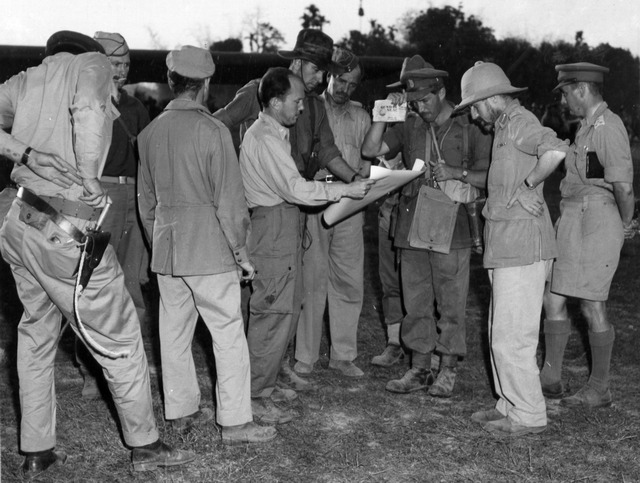

The group photo above is one of the most dramatic images of WW2. Taken at Lalaghat airfield in India on 5 March 1944, it shows an Allied operation at a critical go/no go moment. American glider pilots are waiting to spearhead a British invasion of Japanese-occupied Burma. Zero Hour is half an hour away. Suddenly, last minute news causes consternation. Worried senior officers standing by the wing of a glider cluster round a man who is holding a blowup of an aerial photograph. It shows that one of the jungle landing zones has been blocked by tree trunks, and is unusable. It raises the possibility that the Japanese are waiting in ambush at the other LZs to massacre the glider troops as they land.

The dilemma – to go, or not to go?

The bearded man in the pith helmet in the group photo is Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate, commander of the Chindits, a British long range penetration force. Designed to operate far behind Japanese lines, its aim was to cut supply routes and create havoc. In 1943, the Chindits’ first, arguably unsuccessful, campaign nevertheless caught the imagination of the press and public. Some hailed Wingate as a visionary genius, although many staff officers rated him a charlatan and a menace. More significantly, Wingate caught the attention of Winston Churchill and the American Chiefs of Staff, who gave him carte blanche to design his own ‘Special Force’.

Wingate was authorized to launch a much bigger repeat performance in Burma in 1944. As before, his troops would be supplied by air, but this time the air component was amplified. Whereas in 1943 his men had marched into the jungle, most would now be flown in, in an operation codenamed Thursday. The Americans gave Wingate his own private air force, manned by Americans, and equipped with Mustang fighters, B-25 gunships, C-47 (Dakota) transports, helicopters, swarms of light aircraft, and Waco gliders. This force was called 1st Air Commando Group, and was commanded by a charismatic and dashing fighter pilot, Col. Philip Cochran. Described by one Chindit officer as “untidy” (which made him a match for Wingate), Cochran wore his cap at a jaunty angle on the back of his head. In the group photo, with his back to the camera, Cochran looks at his deputy, Col. John Alison, who is showing the aerial photo to Chindits Lt. Col. Walter Scott and Brig. ‘Mad Mike’ Calvert (touching his visor). Alison, Scott and Calvert had a particular interest in the outcome of the dilemma, as all three were to be in the first gliders to land.

Calvert was CO of 77th Brigade, the first of several brigades due to fly in. The plan called for his advance troops to land by glider in two jungle clearings codenamed Piccadilly and Broadway. There, aided by American engineers with bulldozers, they would clear runways long enough and smooth enough for C-47s to land, bringing thousands more troops. Scott was CO of 1st Battalion King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. His men would patrol the perimeter and be ready to defend the burgeoning air strips, while also pitching in to help with any task that needed doing.

The man in the group photo self-consciously tucking in his shirt is Lt. Charles Russhon, who took the aerial photos of the LZs only hours before. Flying over the LZs in a B-25, Russhon found that Broadway was clear, but Piccadilly was blocked. He was so shocked by what he saw, that at first he forgot to take photographs, and he had to make another pass. Unable to notify HQ, he then raced against the clock to get the films back to base, developed, printed and delivered, still wet, to the assembled officers.

Scott recounted how “An intense silence broke on everybody in the vicinity … as full realisation of what had happened dawned on us”. Lt. Gen. Slim, CO of 14th Army and Wingate’s boss, was standing apart from the others. Wingate conferred with him. Later both men claimed they had been the one who had come up with arguments in favour of going ahead, and was responsible for making the choice. Slim wrote, “I felt the weight of decision crushing in on me”. Scott recalled that Wingate “turned away, head down, hands behind his back. He looked a forlorn and lonely figure”. Wingate had discussions with Calvert and Cochran, among others, and it was agreed that Piccadilly had probably been blocked because it was known to the Japanese, having been used the year before. Broadway was new and had not. A third LZ was also clear, but Calvert argued against using it. Wingate reported in oracular style: “I, therefore, decided to start with Broadway alone”. Operation Thursday was a go.

Crews destined for Piccadilly now had to be rebriefed for Broadway instead, but take-offs began at 18:12, only 72 minutes late. To maximise the troops and equipment delivered, it had been agreed, after much debate, that each plane would tow two gliders. The tugs had to climb to 8000 feet to get over intervening mountains. The gliders were heavily overloaded, and the double tow put extra stress on the tow cables, some of which simply snapped. Six gliders came down in Allied territory, and eight more behind Japanese lines.

Arriving at Broadway after dark, the first gliders discovered the LZ was not as clear as it appeared in aerial photos. Hidden in the long grass were logs, tree stumps, and deep ruts gouged by elephants dragging teak logs. The plan was that the gliders would be moved out of the way as soon as they had unloaded. Some were intact and pulled aside, but others had lost their wheels, and were impossible to move. Inevitably, following gliders crashed into those ahead. Two gliders undershot and crashed into dense jungle, killing almost everybody aboard. Alison and his men frantically moved flare pots to light alternate approaches, but it was almost impossible to keep ahead of new arrivals. At least there was no sign of the Japanese.

Calvert had agreed two status codewords that could be transmitted in clear. Their theme, perhaps intended to be humorous, was sausages. ‘Soya Link’, a much-disliked vegetarian type, meant ‘Trouble at Broadway – send no more gliders’, while the much-relished ‘Pork Sausage’ meant success. At about 2:30am the only radio, which was damaged on landing, was persuaded briefly to work. Surveying a scene of multiple crashes in the darkness, Calvert sent ‘Soya Link’.

To Wingate and the senior officers sweating in agonies of suspense back at Lalaghat, any humour in the phrase must have tasted sour, now that their fears had come to pass. They assumed the Japanese had attacked and possessed the LZ. Nine gliders of a second wave still en route were recalled.

One tug did not get the message. On landing, the glider crashed between two trees, losing both wings. The impact caused the bulldozer it was carrying to break free and shoot forwards. The Waco’s nose, including the cockpit seats, swung up out of the way, and the crew were uninjured as the dozer passed beneath them.

Dubbed “a freak glider crash” at the time, it was not a miracle but a feature of the Waco, designed to allow a jeep in the glider to automatically raise the nose by starting to drive out. It seemed like a miracle to Calvert, however, as the American engineer who survived the landing with his dozer assured Calvert he could have Broadway ready to receive C-47s by evening. Calvert signalled ‘Pork Sausage’.

Things were not as bad as they had seemed in the dark, and in fact very few men had been killed on the LZ itself. 35 out of 61 Wacos launched from Lalaghat had landed at Broadway, and Calvert’s garrison now numbered some 350 men. The runway was ready for C-47s, as promised, and the first one of many touched down an hour after dusk. On board, presumably fortified by the pleasure of a gamble that had paid off, was Wingate himself. The decision to go had been vindicated.

.

.

.

Thanks to the US National WWII Glider Pilots Association for inspiration and assistance. All images are from US National Archives, except USAF from US Air Force Historical Research Agency.

A version of this article appeared in “Glider Pilot’s Notes”, the magazine of the Glider Pilot Regiment Society.