American tug pilots in Operation Ladbroke were roundly condemned for unilaterally releasing their gliders, many of which landed in the sea off Sicily. Is there more to the story? Previously unpublished evidence helps clarify an enduring mystery.

Squadron Leader Lawrence Wright was Operations Officer of 38 Wing RAF (British Royal Air Force). The Wing provided the Albemarle and Halifax aircraft which towed many of the gliders of 1st Air Landing Brigade to Sicily during Operation Ladbroke on 9 July 1943. All gliders not towed by 38 Wing were towed by American pilots.

Wright wrote about his experiences in 38 Wing in his book “The Wooden Sword” (1967). He comes across as an authoritative, intelligent, urbane, witty and credible witness. However, one of his statements in the book is potentially misleading, yet it has often been repeated, and it has become a key component in one of the sore points of the operation. While listing the many reasons why so many gliders ended up in the sea, he wrote:

“At least ten tug pilots had themselves released the ropes, and only one of these gliders reached land. In 38 Wing there was an unwritten law (and it was observed on this operation) that the rope was never released at the tug end, except in dire emergency.”

Without explicitly mentioning Americans, Wright is nevertheless explicitly claiming that it was American tug pilots, not British ones, who released the ropes. Wright also implies that these American releases were the cause of 90% of these gliders ending up in the sea. His statement has been taken to mean that American pilots who released their gliders were especially culpable, and that this was a major cause of the tragedy of drownings that befell so many glider troops. For most glider pilots and soldiers, many of whom could not swim, and whose lives depended on the pilots of their tug plane, being forcibly released in the wrong place, to land in the sea, probably did indeed seem an outrageously culpable act.

At the heart of the issue is the fact that either the tug or the glider could unilaterally release the tow rope at their end, thus breaking the towing connection. This left the heavy rope either trailing behind the powerful tug, or hanging from the front of the engineless glider.

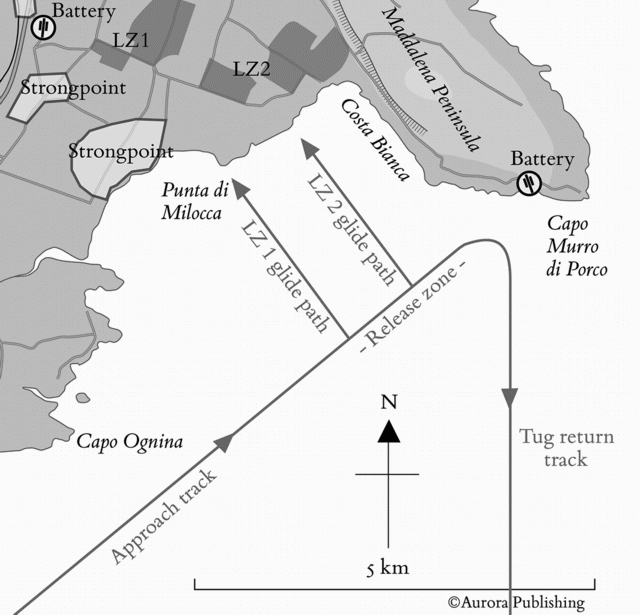

Also central to the Ladbroke story is the fact that the glider release point was set at 3,000 yards (nearly two miles) offshore, in order to keep the tugs safe from Italian anti-aircraft fire. This was done primarily because the Allies had a great shortage of transport aircraft for airborne troops, and they were all needed for airborne operations on the following days. The tugs may have been safe 3,000 yards out to sea, but for a glider the margin for error was slim, and those that were released much further out than this, or too low, had little or no chance of reaching land. Control of that margin for error was out of the glider pilots’ hands, as the tugs were responsible for navigation to the release point.

Statistics

The tugs were provided by both American and British squadrons. Gliders numbered 1 to 54a were towed by the 60th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) of the American 51st Troop Carrier Wing (TCW), while gliders 55 to 104 were towed by its 62nd TCG. The remaining gliders, 105 to 135, were towed by two British RAF squadrons, 295 and 296 of 38 Wing. There was considerable rivalry between the American and British contingents. All the troops in the gliders were British, as were the great majority of glider pilots, although some American volunteers flew as glider co-pilots.

Wright got his figure of ten gliders from the debriefings of the tug pilots conducted by 38 Wing, along with debriefings of glider pilots or, in their absence, their senior surviving passengers. The debriefings were conducted by 1st Airborne Division. Taking these together with other sources not used by Wright produces totals that are higher than Wright’s. Debriefing reports and personal accounts allow at least 22 apparently forcibly released gliders to be identified by number: 5, 17, 21, 22, 26, 30, 31, 32, 33, 37, 38, 39, 45, 53, 53a towed by 60 TCG (total 15), and 56, 64, 68, 69, 71, 81, 96 towed by 62 TCG (total seven). A summary report produced by 60 TCG on 17 July says a total of 15 gliders (which agrees with the identifiable total) were released by the tugs in that group alone. The equivalent report by 62 TCG doesn’t mention releases by tug at all.

Of the 22 identifiable gliders, eight reached land (5, 26, 33, 37, 38, 45, 69, 81), leaving 14 in the sea. These 14 represent only about a fifth of all those gliders that landed in the sea. Clearly, being released by the tug did not of itself cause a glider to land in the sea, and most of the gliders that did land in the sea did so for reasons other than simply being unilaterally released by the tug.

Note that these figures do not include the cases where glider pilots released when their tug took violent evasive action they could not follow, or when they were ordered by the tug to release, even though they thought they shouldn’t. On the other hand, there were also some cases where glider pilots argued against releasing when ordered to by the tug (but only if their intercom was working, and many weren’t), and as a result they were not released by the tug, later releasing themselves.

Accounts

All of the identifiable releases by tug were made by American tug pilots, not RAF ones, which allowed Wright to make his comment about unwritten RAF rules being observed by RAF pilots. It seems nobody told the American pilots about the unwritten rule. In fact, quite the reverse. In an account written a few days after the operation, Flight Officer Michael Samek, an American volunteer co-pilot in Waco glider 99, recalled being told at a briefing that if the glider did not release when ordered to by the tug, it would be released by the tug. He was also told this could cause the rope to snap back and damage the flimsy canvas, plywood and pipe-work Waco glider. This happened to Waco glider 5, piloted by Staff Sergeant George Redway: “I reached out for the release lever but before I could manipulate it the rope came flying back, the heavy attachment at the tow-plane end smashing through the bottom of the cockpit of the glider.” Glider 5 did make land, but only by about ten feet.

More serious is what the 60 TCG report of 17 July says happened to glider 39: “[Tug] #39 cut when S/L [searchlight] on Maddelena peninsula flashed on a/c. [aircraft] rope cut back clipping port elevator – dove out of control, landed in water.” It is not known how reliable this account is, as it contradicts an earlier statement. It also implies a catastrophic descent, but at least one man seems to have survived, glider pilot Staff Sergeant John Ainsworth. According to his commendation for a Military Medal, he swam ashore, knifed two sentries, took a rifle and fought throughout the battle. However the commendation also mentions other survivors, and in what appears to be Ainsworth’s debriefing report, no mention is made of such a crash. An extensive investigation was later conducted into the gliders that ditched in the sea or burned, in order to find out what happened to the men reported missing, so that their families could stop agonising. The National Archives in Kew have investigative reports on nearly 60 Ladbroke gliders, but there is no sign of one for glider 39.

In Samek’s case, the threat of damage from a cable backlash, plus fear that hanging on would disrupt the element (an element was a formation of four gliders which were all meant to release together), was enough to make glider 99’s pilots release themselves when ordered to by the tug. Samek says they did this even though they could not see any landmarks indicating that they were at the correct release point. The whole element of four gliders ended up in the sea, by some accounts four or five miles offshore.

The US tug pilots certainly seem to have felt no shame in revealing that they had released their gliders. The debriefing record for the pilot in the C-47 towing Redway’s glider 5, said:

“He had notified the glider to cut loose twice; so he finally cut the glider loose at the last possible place at 22:12.”

Other records were similar:

“Pulled up after they saw that they were too far out. Went up then to 2000 feet and released glider while on the turn.”

“His glider would not release; so he cut it loose at 22:45.”

“They were not in communication with their glider and had had to cut him loose.”

The gliders from two of these tugs ended up in the sea: one landed half a mile from shore, while the other was one of several which

“landed in the water at distances from coast which made estimate of these distances impossible”.

At the time of the debriefing, when the tug pilots made these statements, it was believed that the percentage of accurate releases and successful glider landings was very high. The disastrous magnitude of the sea ditchings emerged only slowly. The tug pilots must have felt shock and guilt when they later learned what had really happened. They were, after all, only young men of a mainly citizen army, prone to enthusiasms, fears and hopes, just like the troops they transported.

Orders

Samek’s claim about being briefed that the tugs were under orders to release is backed up by documentary evidence. Lieutenant Colonel George Chatterton, commanding officer of the glider pilots, later cited a pre-invasion instruction: “In event of failure to release, tug will release glider on approaching coast running N.W. to S.E. from LZs”. This coastline was the Costa Bianca on the south-west side of the Maddalena Peninsula, and its line marked the furthest boundary of the release run.

Further, the Operation Instruction (OI) issued to 296 Squadron of 38 Wing (the RAF Albemarles) on 8 July stated: “Towropes will be dropped immediately after releasing gliders. If the glider pilot has not released when the end of the ‘release leg’ is reached, the tug pilot will release the cable.” The first sentence about dropping the ropes is identical to one in the Field Order (FO, the US equivalent of an OI) issued on 7 July by the American 51 TCW to the American tug pilots.

This is not surprising, as 38 Wing was under the command of the 51 TCW, and the RAF OI was apparently based on the US FO. However the second sentence is absent from the FO. This implies that the written requirement for tugs to release gliders was introduced by the RAF, even though it surely originated higher up the chain of command. Somewhat surprisingly, Wright himself, author of the comment about the unwritten rule, signed this OI.

When it comes to undermining Wright’s assertion in his book, however, it gets worse. A contemporary post-op report by 296 Squadron (British Albemarle tugs) admitted, without any sign of it being a problem:

“Gliders released mostly on the first run, others on the second or third runs on receiving the order by intercommunication or signal light from the tug, or were jettisoned by the tug pilot”.

The phrase slips into the list so innocuously that it bears repeating: “Gliders … were jettisoned by the tug pilot“. This directly contradicts Wright’s claim about the unwritten rule. It means that British tug pilots as well as American ones released gliders unilaterally. So either the rule did not exist at this stage of the war, or it was disregarded by British as well as American pilots.

Given the instructions in their orders, it could be argued that the tug pilots would have been more culpable if they had NOT released their charges when they thought they should. After all, they had been explicitly ordered to release them, a fact not mentioned by Wright in his comment. Nevertheless, with so many lives at stake, perhaps the tug pilots should have tried longer and harder to ensure the safety of their gliders, by getting to the right spot before releasing them. Some did, after going around for second, third or more passes. Unfortunately, some did not.